Download in pdf format: PBB Jan 2018 – Oct 2019 EN.pdf

Published: 20 November 2019

In Brief

Numerous political arrests have taken place in 2018 and 2019 as the Indonesian authorities attempt to suppress political protests in West Papua and Indonesia. In particular, treason charges have been used to an unprecedented extent to arrest political activists during August and September this year, in response to an apparent increase in support across Indonesia for the West Papuan self-determination struggle. Foreign as well as local human rights advocates are being subjected to similar scrutiny.

Papuans Behind Bars (PBB) documents and identifies Papuan political prisoners/ detainees in order to bring to light their cases, and also monitors for fair and free trials. The people involved in gathering the data are lawyers from non-profit, independent legal aid institutions in West Papua who also provide legal assistance to political prisoners, human rights advocates and activists. They collaborate so as to get accurate data on the prisoners/detainees. PBB also analyses the consistency between the data it collects and any reports in the media. Most of these cases, however, are not reported in the media.

Political Prisoners and Detainees January 2018 to October 2019

- • Imprisoned for the third time for peaceful activism: Buchtar Tabuni, Steven Itlay, and Yanto Awerkion

- • First West Papuan women charged with treason since 2000: Ariana Lokbere and Sayang Mandabayan

- • First foreign national charged with treason: Jakób Skrzypski

- • First non-Papuan Indonesian activist charged with treason: Surya Anta Ginting

- • First non-Papuan Indonesian human rights defender criminalised over West Papua advocacy: Veronica Koman

- • First journalist/documentary film-maker criminalised for tweeting about West Papua: Dandhy Laksono

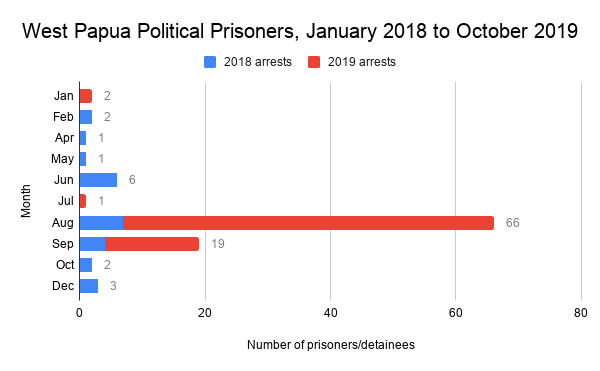

In total, from January 2018 until October 2019 there have been 99 West Papuan political prisoners/detainees.

In 2018, PBB documented 26 political prisoners detained in West Papua: 25 West Papuans and one Polish national. The majority of the West Papuan detainees were charged with possession of firearms, although two among them were charged with treason. Some of these prisoners have now been released or are due for release later this year or early in 2020.

For the first time, a foreign national has been detained in a West Papuan prison. The police arrested a Polish national, Jakób Skrzypski, in August 2018 for ‘conducting journalistic activities’ but later for allegedly meeting with the West Papua National Liberation Army. He was tried for treason for a few lines of chat on Facebook Messenger with a West Papuan student, who was also tried for treason together with him, regarding firearms. Mr. Skrzypski denied all the accusations and filed an appeal to overturn his case but this was denied. He is currently serving a 5 year sentence in Wamena prison.

In 2019, there has been a surge in the number of West Papuan political prisoners/detainees. PBB has identified around 77 new political detainees in cases related to West Papua this year. Most detainees were arrested for their involvement in the mass civilian demonstrations during August and September. Most of them were arrested on charges related to their participation in rallies, which turned violent in some places. Some were detained for treason and others are being criminalised for taking part in broadcasting the protests in the media.

Treason Charges

2019 shows a significant increase in treason charges: 22 compared to 5 in 2018. Out of the total of 27 treason charges during 2018 and 2019, 25 were arrested for taking part in peaceful assembly and political protests. Three treason suspects in 2018 were arrested while carrying out a traditional cooking feast and praying ceremony at the Timika office of the West Papua National Committee (KNPB). Meanwhile, the 22 treason suspects in 2019 were arrested for taking part in political protests during the August-September period. This shows that the Indonesian authorities are using treason charges to silence free political expression, a right that is guaranteed by the Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia.

Members of political rights organisations such as West Papua National Committee (KNPB), United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP), Papuan Student Alliance (AMP) and Indonesia People’s Front for West Papua (FRI-WP) are the target for treason charges because they are voicing the West Papuan rights to self-determination. Among the list of the 22 detainees charged with treason in 2019 are Agus Kossay, Chair of KNPB, and other key figures of the non-violent movement, Buchtar Tabuni and Steven Itlay. Others include student leaders Fery Gombo and Aleksander Gobai, and Surya Anta Ginting, the spokesperson for Indonesia People’s Front for West Papua (FRI-WP).

Transfer of Political Prisoners

On 4 October, the police transferred seven of eight political prisoners in Jayapura, charged with treason, to police detention in East Kalimantan. Lawyers for these seven political prisoners stated that the transfer was unlawful as it violated Article 85 of the Criminal Procedural Law. This determines that suspects can only be transferred after investigation processes have been completed and filed with the District or State Prosecutor’s Office, and only the Prosecutor’s Office can authorise the transfer of suspects under certain circumstances.

The transfer is considered as an act of isolation from the prisoners’ community and culture. In this case it is also removing them from their rights to access legal assistance, given the difficulties that legal aid institutions face across Indonesia.

Challenges for Political Prisoners Advocacy

Advocating for political prisoners in West Papua is very challenging due to the following circumstances:

- • Limited legal aid resources

- • Limited judicial transparency and accountability due to the political circumstances

- • Lack of freedom for human rights defenders/lawyers to carry out their roles

- • Lack of independence of judges in ruling on West Papuan political cases

- • Criminalisation of activists as a new method by the State to oppress civil and political rights advocacy.

Limited legal aid resources:

Due to the political and geographical situation, legal aid resources in all the territories of West Papua can only provide limited legal coverage. There are only a handful of legal aid institutions that are trusted by the West Papuan political detainees. They are the non-profit legal aid institutions which have been providing legal assistance to political activists over the years. Secondly, due to their geographical isolation, most political prisoners must often wait several days after arrest before they get assistance from their lawyers. Depending on where they are located in West Papua, most of the time the lawyers need to fly to get to their client’s location. On top of this, these legal aid institutions have only limited resources and means for travel.

Limited judicial transparency and accountability due to the political circumstances:

There are breaches to the criminal procedure in almost every arrest documented by PBB, meaning that often political prisoners are being interrogated without any lawyers present. The authorities can also make it harder for lawyers by moving the detainees around (see Box: Transfer of Treason Suspects Mirrors Colonial Behaviour).

Many arrests and detentions have been characterised by breaches of proper procedures, wrongful convictions, ill treatment, and torture. Improper procedures have included cases where an accused individual was not afforded legal counsel during interrogation or at trial, was not presented with an arrest warrant at the time of arrest, or was subjected to torture. In some cases, activists were subjected to multiple breaches. For those who were sick or shot, their access to treatment was impaired. In many cases, police or military personnel employed excessive use of force during the arrests of the political prisoners documented in this report.

Lack of freedom for human rights defenders/lawyers to carry out their roles:

There have been clear threats against human rights defenders/lawyers in West Papua in the last couple of months. The Indonesian authorities are attempting to criminalise human rights lawyers/defenders for their involvement in the advocacy for civil and political rights of the West Papuans. Action against Veronica Koman, Surya Anta Ginting and Dandhy Laksono are the latest examples of this. These criminalisation methods are the State’s attempt to limit human rights and civil liberties in Indonesia and particularly in West Papua.

Lack of independence of judges in ruling on West Papua political cases:

Lawyers acting for West Papua political prisoners complain that judges tend to be partial when ruling on West Papua political cases. For instance, a judge in Timika read out a pre-prepared ruling on the case of KNPB activists Yakonias Womsiwor and Erichzon Mandobar immediately after their lawyer had finished delivering the second defense on 13 May this year. Judges failing to include the lawyers’ defense, except for a line or two, in the ruling’s consideration is also a common practise in West Papua political cases.

Criminalisation of activists as a new method by the State to oppress civil and political rights advocacy:

Following the release of five West Papuan political prisoners in 2015 during President Joko Widodo’s first term as President, treason was no longer frequently used against West Papuan activists. Then in 2018 there were 5 cases, and in August and September this year there were 22 cases.

This does not mean that judicial harassment against peaceful West Papuan activists has stopped. Activists are still targeted with charges which are politically-motivated. For example, high profile activist Bazoka Logo was accused of falsifying an identity document, and KNPB activist Sam Lokon was wrongly convicted for stealing a motorbike. Deeper analysis is now required to look into such cases which go beyond the usual charges of treason or incitement.

Overall, the situations mentioned above create a lack of judicial transparency for all political prisoners in West Papua. This makes advocating for political prisoners in the territory more challenging than ever. The Indonesian Government has failed to fulfil its duties and responsibilities to maintain judicial transparency in West Papua when it comes to political cases. Rushed judgements, failure to observe the judicial procedures, and threats against legal advisors are all evidence of the lack of judicial impartiality in West Papua, which opens up even more room for error and abuse in the treatment of political prisoners.

Transfer of Treason Suspects Mirrors Colonial Behaviour*

By Anum Siregar

Jayapura – On 4 October 2019, the Papua Regional Police moved 7 treason suspects, namely Buchtar Tabuni, the chairman of the West Papua National Committee (KNPB) Agus Kossay, Fery Combo, Alexander Gobai, Steven Itlay, Hengki Hilapok, and Irwanus, from Papua Regional Police detention to East Kalimantan Regional Police detention. The legal advisor of the suspects found out only on the morning of departure, when contacted by one of the investigators, and then by mail delivered later the same day. This was despite the fact that, the day before, the lawyer for Buchtar Tabuni et al visited the suspects and met with investigators, but there was no notification whatsoever regarding a transfer.

Procedures set out in the Criminal Code Article 85 on Transfer of Suspects:

“In the event that a regional situation does not allow a district court to hear a case, then at the suggestion of the head of the District Court (DC) or the head of the State Prosecutor’s Office concerned, the Supreme Court (SC) proposes that the Minister of Justice establish or appoint a district court other than the one stated in Article 84 to try the case in question.”

This article confirms that the Chairperson of the District Court or the Public Prosecutor’s Office has the right to transfer a suspect for the benefit of a trial, once the Police investigation process has been completed, and the suspect or Suspects and their case files have been transferred to the Prosecutor’s Office to wait for the trial process. The investigators, namely the police, are not authorised by the Criminal Code to move suspect on the grounds of the interests of the trial.

However, in the case of Buchtar Tabuni et al, having already been questioned by the Papua Regional Police, most of them were detained for more than 20 days, followed by an extension of 40 days, and were then moved while still at the investigation stage. The suspects have not been transferred to the local Public Prosecutor / Attorney’s Office.

In terms of investigation management in the Place of Detention Transfer Order number SP.Han / 381.g / X / RES.1.24 / 2019 / Ditreskrimun dated October 4 2019, there were irregularities.

First, a letter was issued by the Criminal Investigations Department for the purpose of transferring suspects to a different Regional or Provincial Police detention centre. The authority to give this approval rests with the National Police Headquarters, but the transfer was made without the authority of a letter from the National Police Headquarters as a basis of the transfer. Even the National Police Headquarters said that they did not know anything about the transfer, whereas the Head of East Kalimantan Police Public Relations Commissioner Ade Yaya Suryana, confirmed that the transfer authority rests with the National Police Headquarters.

Second, one of the basic considerations of the letter is the Papua Police Chief’s letter number: R / 205 / X / RES.1.24 / 2019 / Ditreskrimum dated October 3, 2019 regarding Requests for Safekeeping of political prisoner treason suspects. However, it did not explain to whom the letter was addressed; whether to the Supreme Court, the National Police Chief or the East Kalimantan Regional Police Chief.

Third, there is no basis for a letter relating to the Decision of the Supreme Court or a letter from the National Police Chief, as a basis for the transfer. This means that the Police have violated the provisions of Article 14 paragraph (1) letter 1, Law Number 2 of 2002 concerning the Indonesian National Police, which emphasizes “In carrying out its main tasks, the National Police of the Republic of Indonesia performs its other duties in accordance with statutory regulations.

The transfer of Papuan prisoners / political prisoners began with prisoners / political prisoners of the Wamena incident in 2000, if not earlier, when Pastor Obeth Komba et al were accused of treason. They were undergoing trial at Wamena District Court. After being convicted in Wamena prison they were then moved to Jayapura without notification of the family. At that time there was concern that they would be moved out of Jayapura. Following communication between the family, the Lawyers Team and the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, they served their sentences in Abepura prison.

Linus Hiluka et al, convicted of the Wamena military command ammunitions store raid in 2003, were transferred to the Gunung Sahari Makassar prison in 2004 after undergoing trial at Wamena District Court. They were then sentenced in Makassar. In 2007, Maikel Haselo, one of Linus Hiluka‘s colleagues died and his body was brought from Makassar to his village in Anjelma Kurima, Yahukimo. In 2009, Linus et al were moved to Nabire Prison and Biak Prison. At that time the Papuan People’s House of Representatives Commission F played an important role in their transfer to Papua, including the repatriation of Maikel Heselo’s body.

In May 2015, they received clemency from President Joko Widodo.

In 2004, still related to the Mile 62-63 incident in Timika, Antonius Wamang and 12 of his friends were arrested in Timika and then flown to Jayapura on the same day. They were immediately investigated by the Police Headquarters Team at the Papua Regional Police on the same day. 8 of them were named as suspects and 4 were released. The day after that, they were immediately flown to the National Police Headquarters to undergo further investigation as suspects. There were no investigations for days, then later they were transferred to another location.

In addition, stories about the pre-trial transfer of political / treason prisoners in Papua cases very often emerge, but the transfers take place only after the suspect and the case file has been transferred to the public prosecutor / attorney’s office. As happened in the case of the alleged treason of Areki Wanimbo in 2014, Areki Wanimbo, a Lanny Jaya tribal leader was arrested at the end of August 2014 in Wamena, underwent examination at the Papua Regional Police in Jayapura, and was then tried at Wamena District Court after the case file was submitted to the public prosecutor / Prosecutor. Both Jakób Fabian Skrzypski, arrested in August 2018 in Wamena, and Simon Magal, arrested in August 2018 in Timika, underwent examination at the Papua Regional Police in Jayapura and were then transferred to Wamena after the case file was transferred to the Public Prosecutor / Attorney’s office. Once again, all of these transfers were different from those experienced by Buchtar Tabuni et al, who were moved while still undergoing the investigation process and without proper procedures.

Regardless of whether the transfer followed procedure or not, it is very clear that these transfers always have a very strong political dimension. This practice actually occurred in the previous colonial era in 1945, when the Dutch exiled Indonesian independence fighters to remote areas, for example the exile of Bung Hatta, Sutan Syahrir, Sayuti Melik etc. to Boven Digul. This exercise of political power is not a legal approach. In the past, there were political prisoners who were exiled from Batavia to Holandia (Papua). Now political prisoners are exiled from Holandia (Papua) to ‘many places’ in Batavia (Indonesia).

Although for today’s political activists there are existing legal proceedings, these transfers are acts of isolation, punishment and even exile, so that they are far from their communities. Isolated from everything that can make them feel ‘they still exist’. By being in a place that does not have a dominant issue such as in Papua, it is hoped that there will be less coverage about them. Media attention or local public support will be limited. The legal process against them will not be on the front page, but just a usual court case for the locals. Whereas in reality, the situation might actually strengthen their hearts and minds (as well as those of the people of Papua) to continue to record the dark and stigmatized past as experienced by Bung Hatta et al.

This policy is certainly not appropriate for building trust and good relations between the Indonesian government and the people of Papua. Particularly for improving the very difficult situation today, which requires upholding the law in a professional and fair manner to stop the cycle of violence and maintain peace in Papua.

*This article was first published in Indonesian on Anum’s Facebook on 11th October 2019.